Using the car industry as a model for creating digital service systems connected to physical products.

Digitalization has enabled and is now increasingly forcing, traditionally product-focused industries to shift towards a service-system focus. Digitalization, however, has despite what the increasing number of ads for project management tools leads us to believe. Not made it particularly easy to make that shift. One of the hardest challenges is making informed prioritization in a new and unfamiliar context. Looking at the car industry can guide other industries in creating profitable digital service systems there.

Prioritization is at the heart of any management effort. What happens when prioritizations are consistently made on obsolete or flawed information? When the entire framework used to make prioritizations are outdated?

The success of electrification

The car industry, has successfully been transformed – granted, being pulled kicking and screaming by Tesla – towards electrification. The United States President Biden has set the goal of 50% of electric cars being sold in the US by 2030, Sweden has proposed a ban of fossil full cars all together within that same time-frame.

Political ambitions with regard to electrification are possible because the car industry has seen the need for and potential profits from, making the shift. This has successfully accelerated electrification to the point where a manufacturer of cars needs to have at least a flagship electric model in order to stay relevant.

The perils of servicification

One thing has also been on the agenda for a long time, which has not been as successful. Moving away from selling cars and towards selling mobility. Why have car manufacturers been successful in creating a whole new propulsion system, while simultaneously being so inept at changing how we use our cars?

While electrifying our vehicles requires new technical design and manufacturing capabilities. The same type of product – a car – is still created. Changing to selling mobility is shifting the whole idea of what a car manufacturer is and does. This in turn changes what information is important when making decisions.

When producing any physical product, the number of aspects that need to be taken into account is fairly limited. Let us simplify it to function, form, and marketing. These aspects, such as function – what the product does, and even how it does it – have been long since established. Sure, there might be tweaks to performance or comfort or looks, but largely physical products tend to be fairly static. This is the reality that most product companies, such as most car manufacturers have existed in for more than a century.

New actors

There is another effect of digitalization that is relevant to look at. Suddenly, companies without manufacturing capabilities are able to create new revenue streams, that manufacturers are largely cut off from. A good – and well-used – example is Uber that uses the cars manufactured by others. Creating digital service systems, completely outside the control of Volvo, Ford, and other manufacturers.

Logically then, car manufacturers have spent the bigger part of the last decade trying to close the gap between themselves as producers of physical products and the service economy that Uber and other actors have shown exist. Why have we not seen any large-scale and successful car-sharing, mobility, or transportation services spring out of our traditional automakers?

For one, most resources in these companies are invested in the creation and production of new car models. This makes sense since this is where they make their money. That brings a certain rigidity to the organizational setup. This n turn affects the organizations’ capabilities to focus on creating useful services.

Modern and agile development in a rigid system.

The car industry is – not without reason – used to working inside rigid processes. (When your feature can perform to x safety standard then you will get money to develop y). A car is again, a well-defined product that can be specified in a detailed way even before development starts. “We want a large SUV that caters to suburban females.” This then leads to having a product being launched in 2-3 years that has been specified in detail. Certainly down to what type of components should be included, and probably down to approximately what these components should cost.

Enter the agile design team, tasked with creating a revolutionizing service that will transform mobility. This is a complete clash of worlds. The first thing a designer will want to do is speak to the real users of the future service. This is something almost unheard of in a car company. “Real users, you say? I’m sure we have the number to a motor journalist here somewhere”.

Next, the design team will want to create an agile process where they can iterate ideas until they have a great solution. “Ah” says the car company. “We have plenty of agile teams working on our products!” While this is true, these agile teams all live inside of the rigid processes we visited earlier. This means that the teams are free to arrive at the specified conclusion however they like, but if they want money after that, they’d better make sure they don’t deviate from the specification. No matter what. To be fair, this is not out of any ill will. In order for cars to be sellable, cars need to live up to fuel and safety standards, among other things.

The real difficulty

This is frustrating to our designers. This is also the key to the car industry’s success – after Tesla – when it comes to electrification. So long as the original specification is clear enough it is (relatively) easy to fit batteries and electric motors into the traditional processes that are needed to develop a vehicle. These processes are extremely efficient at producing new cars and handle incorporating these types of technical innovations really really well. The problems start to appear when the produced cars are no longer the end product, but instead a vehicle – if you will – for the service of mobility.

In order to become credible service providers or digital service-platform providers, manufacturers need to commit to setting up an organization where services are able to dictate, through management buy-in, some of the technical requirements on the vehicles to facilitate these same services.

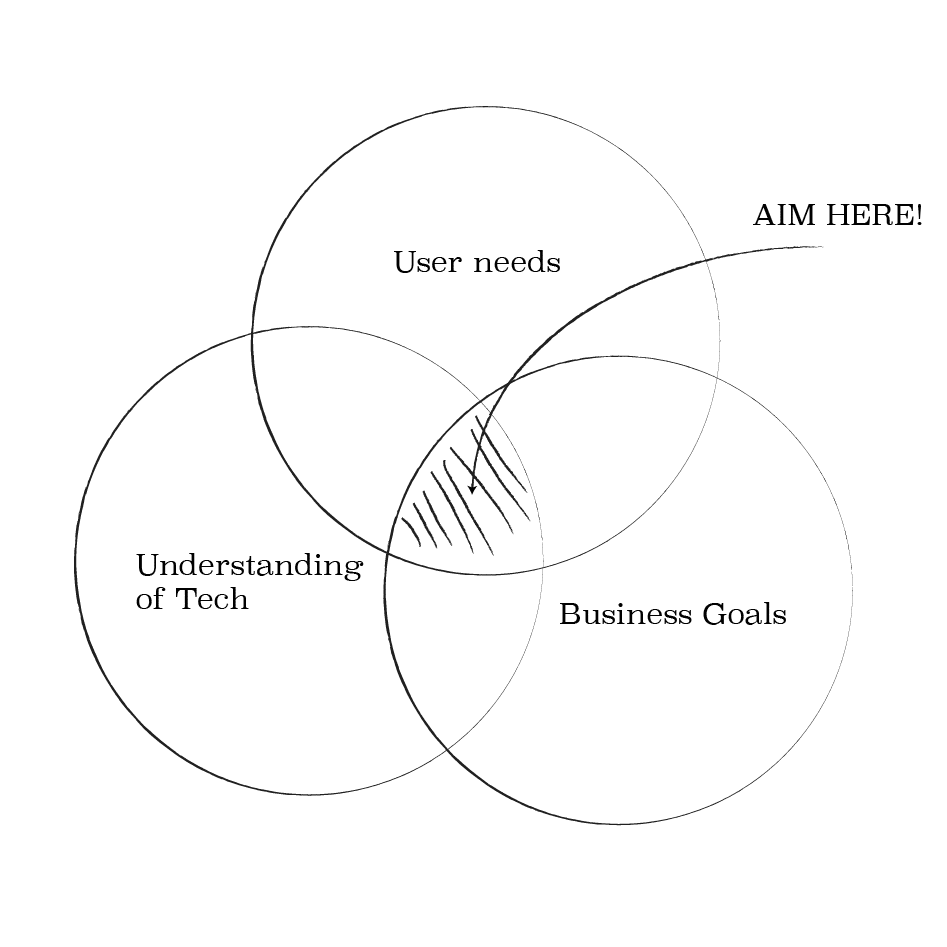

For one, creating digitservice systems around cars changes the demands on vehicles to include connected technology. Connected tech also needs to be robust and up to date for longer than the normal infotainment systems we see today. All this requires new types of information as input to the management of car companies. How digital should a car be to be digital enough? What is the return on investment for turning cars into mobile, over-the-air-updatable computers?

Wider implications

More and more cars are connected to the internet in more ways. More and more aspects of their use and operations will inevitably be taken over by digital services. The question is how the manufacturers of cars adapt to these changes. How much of the new revenue streams manufacturers will be able to tap into. To do that well, the auto industry leaders need to figure out how to incentivize the development of service systems. As opposed to the development of new car models. This will not be easy but will win them the race.

It is time to start looking beyond the auto industry. What we have already learned there, can be applied in other industries that have – up until now – been spared from the hassle of having to create digital service systems. I am guessing that facilities management, manufacturing of consumer goods, medicine, and food production, will have to tangle with the same issues as the auto industry has had to deal with. My hope is that management in other industries will learn from their experience. Hopefully, they will find solutions on how to shift organizational focus towards a digital service system mindset.

This article is an attempt at writing down the essence of several years worth of discussions on the topic with a lot of really smart people both inside and outside the industry. You know who you are, thank you, let’s have a chat soon!

Read more about design and innovation

If you would like to read more about some of the difficulties with innovation and design in general. I have a post on the topic here. It goes into more detail about prioritization when it comes to innovation efforts.

Cover photo by Laurie Decroux on Unsplash